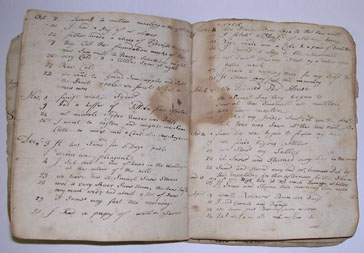

Like the records he left, Colonel Samuel Pierce’s major concerns focused on the patterns of daily life—farming tasks and cycles, the weather, kin and community relationships, improvements to his family home—he was also deeply engaged by the world around him. Pierce was an astute observer whose commentary on the American Revolutionary era brings to life the events of this crucial period in American history. Participant as well as observer, Pierce made his political sympathies clear. An early supporter of the patriot cause, he resigned his commission in the King’s militia to join the Massachusetts militia and took part in what Dorchester historians view as a crucial step in the United States’ war for independence: the fortification of Dorchester Heights and the forced evacuation of the British troops from Boston in March of 1776. He led his regiment for the duration of the war.

During the ten years between 1765 and 1775, a series of political conflicts between Great Britain and her American colonies contributed to the breakdown of the imperial relationship, the outbreak of armed conflict between patriot and loyalist troops, and the eventual declaration of independence by the new United States. Because Boston was a center of colonial protest, Britain tried to make the town an object lesson in imperial authority, and from nearby Dorchester, Col. Samuel reported his personal politics and involvement in the town’s growing support for the patriot cause. All through New England the Sons of Liberty had formed in 1765 in opposition to the Stamp Act, and Col. Samuel recorded that they met in Dorchester at a “very Grand Entertainment at mr. Lemuel Robinson’s” in August 1769. The Pierce family also held patriotic events at their home, including a “spining match” held “at our house” in June of 1769. Such gatherings were part of the colonists’ campaign to produce and wear their own homespun clothing rather than rely on English imported goods.

From Dorchester Col. Samuel observed the unfolding of events in Boston. On March 6, 1770, the day following the Boston Massacre, he noted “four kild in boston by the Soldiers.” He also recorded the growing support of the Dorchester citizenry for the colonial protest, as evidenced by a town meeting in December of 1772 “to Exclaim against the Duty being Laid upon us & Judges having their Saliry paid from England &c.” Pierce also followed the controversy over the Tea Act of 1773 closely. England had granted what colonial merchants termed an unfair advantage to the East India Tea Company’s virtual monopoly and the fact that Parliament had levied a tax on tea in the first place. Many colonists resolved to boycott tea, but a large supply arrived in Boston late in 1773. “Boston,” observed Pierce in his journal on December 11, “is full of trouble about the tee. . .,” and several days later Boston radicals orchestrated the Boston Tea Party.

By June of 1774, following the passage of the Intolerable Acts, tensions between the colonists and Great Britain had increased. Colonial self-government and the judiciary were reduced, more British troops and warships arrived, and “Boston [was] in a most Deplorible Condition.” In the fall of 1774 Col. Samuel Pierce and others in the provincial militia had resigned their commissions under the crown and received new appointments as officers in the colonial militia. The following March the town of Dorchester voted that all men fit for military duty should be ready to respond to any alarm on a minute’s notice. When actual conflict broke out at Lexington and Concord in April of 1775, Col. Pierce’s loyalties were evident: “April 19. this Day there was a terible battle at Lexinton & Concord between our People and the Soldiers which marcht out of Boston the Soldiers fird on our people and then the Battle Began & there was about 40 of our People kild & 190 soldiers as near as could be Recolected.”

Over the spring and summer of 1775 Pierce observed and recorded activity in Boston as some Tories from surrounding towns moved into the city and patriots fled. He lamented the “Terrable battle fout at CharlesTown”—the Battle of Bunker Hill—and noted various “scirmiges” with the British regulars, particularly on the Boston Harbor Islands, as each side sought to establish position and to cut off the other’s supply of hay. General George Washington had set up headquarters in Cambridge, with his other troops camped in Roxbury, Somerville, and Dorchester, so that the city of Boston, though held by the British, was surrounded. When the patriot officer Col. Henry Knox arrived with guns and ammunition dragged on sledges from Ft. Ticonderoga, Washington and his advisors decided to act.

Washington’s plan was to fortify Dorchester Heights, now South Boston, and therefore “command a great part of the town and almost the whole harbor.” After careful preparation Colonel Samuel and his troops took part in the expedition that began on the night of March 4, 1776. About 5,000 men and over 380 wagons sneaked onto Dorchester Heights, placing straw along the road to muffle the sound; the men were under orders not to speak above a whisper. The troops carried the tools, materials, and arms for their defense, including bales of hay, barrels of stone and earth, and the heavy siege guns from Ticonderoga. It was, according to Pierce, “the most work Don that Ever was Don in one Night in New England.” When the British commander, General Howe, realized his predicament, he sent word to Washington that if he and his troops were allowed to leave without being fired upon, he would refrain from destroying the city. On March 17, 1776 (still observed in Boston as Evacuation Day), Howe, his 8,000 troops, and approximately 900 loyalists set sail for Halifax. Although Boston had suffered much during the occupation, with buildings destroyed for firewood, troops and horses quartered at will, and hunger rampant, Howe kept his word and did not burn the city. He and his troops left, wrote Col. Samuel, “like so many frited Sheep.” By March 28 patriots were able to “go into boston all freely,” and in Dorchester town meeting pledged in May of 1776, “america Declard Independancy from Great britain.”

For the duration of the war, Col. Samuel Pierce remained in the colonial militia, one of the two separate but complementary military forces that fought for American independence. As commander of the South Dorchester militia regiment Col. Samuel Pierce seems to have held a chiefly administrative position. He dispatched men from his unit to serve with the Continental Army near Boston and, later, in the Middle Colonies and other New England locations. In addition to troop deployment, Pierce handled both payroll and provisions. Pierce did accompany his men on two expeditions, one through New York to New Jersey in 1777 and one to Tiverton, Rhode Island, in 1779, and he also saw active duty on Castle Island in Boston Harbor. During his absence, Elizabeth Pierce, with the assistance of Samuel’s sister Rebecca, took care of the family and managed the farm. In the later years of the war, with fighting concentrated n the southern states, Col. Pierce detached his men for only limited service, but they maintained their role as patriotic citizen-solders until the war ended in 1783.

Neponset

Neponset First and Second Generations

First and Second Generations Third and Fourth Generations

Third and Fourth Generations Fifth Generation: Samuel Pierce Jr. and Elizabeth Howe Pierce

Fifth Generation: Samuel Pierce Jr. and Elizabeth Howe Pierce Sixth and Seventh Generations

Sixth and Seventh Generations Eighth and Ninth Generations

Eighth and Ninth Generations Ninth and Tenth Generations, and Becoming a Museum

Ninth and Tenth Generations, and Becoming a Museum