Hidden Outlet

Hidden Outlet

The Wabanaki word Wiscasset means “Hidden Outlet,” referring to the bend in the Sheepscot River that conceals the outlet of the harbor from the view of someone traveling upriver. This is an example of the centrality of the natural world to the Wabanaki – the place is named for one perspective from the river. Alternative spellings for Wiscasset include Witchcasset, Whiscasset, Whichacasecke, and Wichigaskitaywick. Wiscasset Bay is Abonnesig, or “small resting place.” The Cowseagan/Cowsigan Narrows (where the Sheepscot River separates Wiscasset from Westport Island) means “Rough Rocks”. Aponeg is the part of the river “Where it Widens Out.” Chewonki Neck (down the river from Cowseagan) is the “Big Ridge” and Nekragen/Nekrangen (the mouth of the Sheepscot River) is “The Opening.”

The land, rivers and other waterways have always been integral parts of the Wabanaki identity and culture. They connected, fed and sustained the people’s communities. The natural world and its creation are part of Wabanaki celebrations, their rituals, their art and their music, and are at the core of their belief systems. The Sheepscot River, called Pashipscot by the Wabanaki meaning “channels split by rocks,” was a transportation corridor. The shores of today’s Sagadahoc, Lincoln, and Knox counties are named Wawenock, meaning”inlet places,” and were places of seasonal fishing, hunting and trading.

The Wabanaki, “the People of the First Light,” are the Indigenous Peoples of Wabanakiak, “The Dawnland,” which consists of the places we call Maine, New Hampshire, Vermont, New Brunswick, Nova Scotia, Cape Breton Island, Prince Edward Island, Anticosti, Newfoundland, and the southern region of Quebec south of Saint Lawrence River. By archeologists’ accounts, the Wabanaki have been in this region for 13,000 years; oral history tells us that the Wabanaki have been of these lands since creation. Due to disease, war, dispossession, and the genocidal policies enacted by the United States government, the Wabanaki suffered a population decrease of 96% since Europeans’ first contact with Turtle Island (North America.) The many diverse tribes and bands across Wabanakiak have amalgamated into five principal Nations: the Mi’kmaq (derived from the word “Ni’kmaq” meaning “my kin friends,”) Abenaki (derived from “Wabanaki,”) Wolastoqiyik “People of the Beautiful River” (Maliseet), Panawáhpskek “Where the Rocks Widen” (Penobscot,) and Peskotomuhkati “Pollock-Searing People” (Passamaquoddy.) The Walina’kiak, or “People of the Bay,” were the tribe most associated with Wiscasset.

Conflict and Survival

First continuous contact with Europeans in Maine came in the mid-17th century with French explorers, trappers and traders interested in commerce with the Wabanaki rather than colonization. Merchant ships soon followed carrying Catholic missionaries as well as traders. English colonists began to arrive in increasing numbers in the later 17th and 18th centuries with expectations of sovereignty over all, whatever means necessary.

First continuous contact with Europeans in Maine came in the mid-17th century with French explorers, trappers and traders interested in commerce with the Wabanaki rather than colonization. Merchant ships soon followed carrying Catholic missionaries as well as traders. English colonists began to arrive in increasing numbers in the later 17th and 18th centuries with expectations of sovereignty over all, whatever means necessary.

In 1662, the Wabanaki Sagamore Robinhaud signed an agreement confirming the right of English Massachusetts settlers George and John Davies to possess a tract of land on the west side of the Sheepscot River (now Wiscasset). The Wabanaki saw this as a reciprocal agreement, believing that the settlers would peacefully respect and care for the landscape. The English saw it as their purchase of sole ownership. Colonists dammed rivers and violently drove the Wabanaki from the surrounding land. Within ten years, the resulting series of conflicts swept the Wabanaki into the global conflicts of the French and British empires. Wars between the Wabanaki and British colonists caused most of the latter to flee to southern Maine and Massachusetts where they remained for decades.

On December 2, 1749, a brutal murder occurred which became known as “the Wiscasset Incident”. Sailors from Massachusetts attacked a group of peaceful Wabanaki as they returned from peace negotiations. They killed Saccary Harry and wounded Job and Andrew. Two women traveling with them, including Harry’s wife, reported the unprovoked murder to the local justice of the peace but the attackers fled. Because the victims were from different tribes and related to prominent leaders of the tribes, the Massachusetts government feared widespread reprisals, so they sanctioned prosecution of the attackers. Two were arrested in York, Maine where a mob freed them from jail. The ringleader fled to Massachusetts, was re-arrested, returned for trial but ultimately released. The event triggered the final series of violent attacks that continued until about 1760.

The Wabanaki survived and overcame centuries of repression and disenfranchisement. Today, four Maine tribes comprise the Wabanaki – the Maliseet, Micmac, Penobscot, and Passamaquoddy. The people live on tribal lands and in towns and cities across the State. Each community has its own tribal government, community schools and cultural center. Each manages its respective lands and natural resources. The Wabanaki culture is alive and well. The People of the First Light will always be an integral part of Maine.

Shipping center

In 1729, Massachusetts colonist Robert Hooper began the resettlement of the area by building a garrison fort at Wiscasset point. More white colonists followed, gradually building up what is now the village area. Over the next five decades, the town became a major shipping center with a deep-water harbor that rarely froze over. Wiscasset’s wealth came from international shipping, – owning and building ships, investing in ships and cargoes, trading goods or servicing the shipping business. Maine wood and fish were sent to the Caribbean to feed and build housing for enslaved people on British plantations. The money made there bought fine goods and foodstuffs in Europe that were then imported to New England. Many of those goods and foodstuffs were made and their material grown by enslaved labor.

In 1760, Lincoln County (which extended from Casco Bay to Nova Scotia) and the town of Pownalborough (including Wiscasset, Alna and Dresden) were officially established. With its close ties to Boston, Wiscasset grew into a busy, prosperous and thriving legal and commercial center.

Concord, MA native Silas Lee moved to Wiscasset in April 1789 to open his own law practice. He had just finished his law studies with Judge and Congressman George Thacher in Biddeford, ME. His new wife Tempe Hedge, George Thacher’s niece, joined him five months later. The only other lawyer in Wiscasset at the time was eight years older than Lee and in declining health.

Lee’s legal practice thrived, but it was his investments in local real estate and international shipping that built his fortune. In 1792, he built an exquisite Georgian mansion on Federal Street overlooking the village and harbor and two houses down from the Courthouse. Silas and Tempe became known for their hospitality, entertaining visiting dignitaries, legal and political colleagues as well as friends and family. For the next fifteen years, Silas bought and consolidated all the parcels of land originally owned by colonist Josiah Bradbury on what was called Windmill Hill. There he would build his dream home, the house we know as Castle Tucker.

The Lees and Elm Lawn

The Lees and Elm Lawn

In 1807, Silas Lee built a large brick mansion at the end of High Street in Wiscasset on a hill overlooking the Sheepscot River. Chief Justice of the Court of Common Pleas in Lincoln County and a U. S. Congressman, Lee was one of the wealthiest and most prominent citizens in town. He and his wife Tempe planted two large elms near the house that inspired them to name the mansion Elm Lawn. Built in the Regency style, the house was massive in appearance, with a large central section flanked by two rounded bays. This was to be the Lees’ town house, fit for elegant hospitality and gracious living.

That same year, however, the Jeffersonian Embargo badly damaged New England’s seaport economy. Silas Lee, heavily invested in shipping and real estate projects, was hit hard. He died in 1814 in a spotted fever epidemic, leaving his wife Tempe to settle his debts. She rented out Elm Lawn and built a smaller house on her remaining portion of the land. Wiscasset went from a sparkling boom town to an impoverished coastal village in a very short period of time.

Image courtesy of Bowdoin College Museum of Art, Brunswick, Maine. Gift of Mrs. P. S. J. Talbot.

Multiple Owners and Decline

The house had several tenants, not all of whom have been identified. Architectural changes and repairs made to the house during this period were not documented. In the 1840s and 1850s Wiscasset enjoyed another brief period of prosperity as the cotton trade invigorated shipping once again. In 1845 Franklin Clark, an ambitious local politician and successful lumber merchant, purchased the house and began what appeared to be significant renovations and changes. These probably included moving two of the house’s chimneys to the end of each semi-circular bay, replacing central windows that had previously lit those rooms. However, Clark did not have the money to pay for these changes or any other of his failed investments. He was apprehended by the local sheriff at the train station trying to leave town, fleeing his creditors.

The house had several tenants, not all of whom have been identified. Architectural changes and repairs made to the house during this period were not documented. In the 1840s and 1850s Wiscasset enjoyed another brief period of prosperity as the cotton trade invigorated shipping once again. In 1845 Franklin Clark, an ambitious local politician and successful lumber merchant, purchased the house and began what appeared to be significant renovations and changes. These probably included moving two of the house’s chimneys to the end of each semi-circular bay, replacing central windows that had previously lit those rooms. However, Clark did not have the money to pay for these changes or any other of his failed investments. He was apprehended by the local sheriff at the train station trying to leave town, fleeing his creditors.

Castle Tucker, Country House

Richard H. Tucker Sr. was a successful ship captain and owner who had built a fortune shipping goods from New England and Charleston, South Carolina, to Europe via Liverpool and Le Havre. He and his wife Mary Mellus Tucker lived in a small house on Main Street in Wiscasset, where they raised three children, Richard, Joseph, and Mary. They later built a large brick home in the best neighborhood in town on High Street. Franklin Clark was their neighbor and an occasional business contact of Captain Tucker Sr. After it became clear that Clark was broke and had been less than honest in his business dealings, Tucker urged his eldest son to purchase Elm Lawn from the creditors when it came on the market.

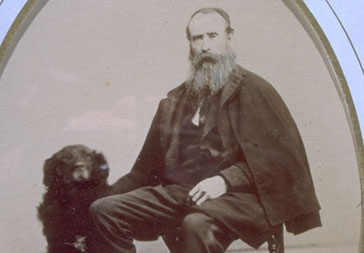

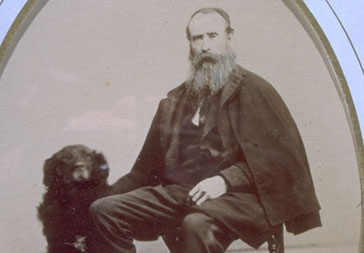

Richard Tucker Jr. (pictured) was born in 1816 and educated at Bowdoin College. By 1857 he was forty-one years old, had retired from active sailing after commanding several ships, and was a successful shipping agent. He had just completed an extended tour of Europe and the United States. In Chicago on his way home from the west coast, he became reacquainted with a Mrs. Mary Armstrong and her lovely sixteen-year-old daughter, Mary (known as Mollie). After less than a year of courtship, Tucker returned to Chicago, where he and Mollie were married. They traveled across the United States for their first year of marriage until Mollie became pregnant. Captain Tucker Jr. decided to take his father’s advice and settle down in Wiscasset. In November of 1858, Franklin Clark’s creditors, John B. Swanton and John Jameson of Bath, sold Castle Tucker to Captain Richard H. Tucker Jr. for the sum of $10,500. By that time, the mansion was listed as a country house in the county records. Richard, Mollie, and their newborn daughter Mame (Mary) moved into the house in November of that same year.

A devotee of tastemaker Andrew Jackson Downing, Tucker quickly began furnishing and decorating his new family home in true Victorian fashion. On one shopping trip to Boston, he purchased most of the furnishings for the ten-bedroom, fourteen-room house. Tucker had everything shipped to Wiscasset, then hauled by wagon up the hill to the new house. The Tuckers moved the entrance to the Lee Street side of the house and added a new Italianate entry way. In 1859 Captain Tucker added a grand three-story piazza and purchased three additional lots adjacent to the estate.

Between 1859 and 1864, Mollie gave birth to four more children, Richard (known as Dick), Martha (known as Patty), Matilda (who died in infancy), and William. Slightly too old to serve in the Civil War, Richard participated in civilian war efforts and served in the Maine State Legislature as a senator in 1861. In 1866, their youngest daughter Jane (called Jennie) was born. Typical of the period, the Tucker children had an intermittent education, but they loved to read and were intellectually curious. They enjoyed childhoods filled with friends, winter skating and sleigh parties, and summers spent sailing, swimming, riding horses, and exploring nearby woods. Mollie and Dick were very musical, playing several instruments. Mame sang and played the piano. All the children participated in amateur theatricals.

By 1870 Richard and Mollie’s marriage had deteriorated to the point where she began contemplating divorce. Their problems were due in large part to Richard’s long absences for business and his numerous investments in experimental steam technology, most of which ended in commercial failure. While he traveled, Mollie was forced to remain home, raising the children and somehow running the house on their ever-dwindling finances. The family endured almost constant bickering and complaining, with Mollie taking her frustrations out on her daughters in letters and in person when they were home.

From 1880 to 1882 the Tuckers moved to Boston to avoid large new taxes levied due to a financial crisis in Wiscasset. In reality, only Captain Tucker based himself in Boston. Mollie committed herself to the McLean Hospital for mental instability. Dick began his first job as an astronomer after graduating from Lehigh University. Mame pursued a stage career, working for a number of traveling theater companies including Buffalo Bill’s Wild West Show. Patty moved to Colorado where she had a successful writing and journalism career. Will worked in insurance in the Midwest. Jennie visited friends and tried out a variety of jobs, including a stint as a private detective. In 1883 Castle Tucker, as it had begun to be known, was the site of a brief family reunion for Patty’s wedding to Will Stapleton. The summer of 1889 was the last time the family was all together at Castle Tucker.

Boarding House Period

Throughout the 1870s and 1880s, Mollie was increasingly hard pressed to find money to pay the many bills at Castle Tucker. She was also burdened with an enormous workload to keep the house running. The Tuckers usually had at least one female servant to assist her, and her daughters helped out during their occasional visits. John Comrie, a British army veteran, worked at Castle Tucker for several decades assisting with the heavier duties on the property, caring for the horses and other animals and acting as chauffeur when needed. However, there were never enough servants to allow Mollie to be a leisurely lady of the house. By 1890 she began accepting summer boarders at Castle Tucker. This was a very common and accepted practice among upper middle-class and even wealthy owners of large homes on the coast of Maine at that time. Maine had been a vacation destination since the eighteenth century.

Throughout the 1870s and 1880s, Mollie was increasingly hard pressed to find money to pay the many bills at Castle Tucker. She was also burdened with an enormous workload to keep the house running. The Tuckers usually had at least one female servant to assist her, and her daughters helped out during their occasional visits. John Comrie, a British army veteran, worked at Castle Tucker for several decades assisting with the heavier duties on the property, caring for the horses and other animals and acting as chauffeur when needed. However, there were never enough servants to allow Mollie to be a leisurely lady of the house. By 1890 she began accepting summer boarders at Castle Tucker. This was a very common and accepted practice among upper middle-class and even wealthy owners of large homes on the coast of Maine at that time. Maine had been a vacation destination since the eighteenth century.

Most of the guests were friends of friends or the family. Discreet advertisements were placed in newspapers in New York and Boston that stated that references would be exchanged. People of the Tuckers’ social class would leave the cities and come to the cleaner, cooler coast for several weeks or a month at a time. During this period, Mollie employed a long series of “girls” recruited from cities about whom she complained continuously in her letters to family. Jennie and Will wrote her letters constantly telling her what to do and how to do it, but only rarely arrived in person to help out.

The 1890s were a very sad time in the family. Patty died after a cancer operation in 1893 at the age of thirty-two. Captain Tucker died in 1895 at seventy-nine after presenting a paper at a Wiscasset Fire Society dinner. Mame died in 1900 at the age of forty-two after a long struggle with alcoholism and addiction.

Mollie took in boarders until Dick insisted that she stop. Jennie moved home permanently in 1905 to help her mother. Mollie died in 1922. After that, Jennie continued the practice of taking in summer paying guests on and off through the 1930s until the automobile became the travel vehicle of choice. Instead of known, relatively genteel summer boarders, guests became strangers who only wanted a bed for the night. This was no longer suitable or safe.

Preservation and Presentation

Preservation and Presentation

Jennie Tucker continued to live at Castle Tucker until her death in 1964. She realized that the family’s thriftiness and relative poverty over the years had resulted in Castle Tucker presenting a unique and almost unchanged look into nineteenth-century life that was important to preserve. She passed on this belief to Dick’s wife, Ruth Standen Tucker, and their two daughters. Mary and Jane had been raised in California, where their father worked at the Lick Observatory. Jennie left the house to them. Jane Standen Tucker moved east in 1965 after a successful career as an accountant in Alaska, the Middle East, and Europe. She moved into Castle Tucker and began to preserve and record her family’s history and the house. Working with Historic New England, then known as the Society for the Preservation of New England Antiquities, and other experts for guidance, she undertook repairs and restorations as she could over the years. Jane opened the house to visitors occasionally, especially during Wiscasset’s annual “Open House Days.” She also entertained in the home, providing many Wiscasset residents with fond memories of time spent here. Jane also established the Wiscasset History Committee, worked with the Wiscasset Library organizing and donating material for their Genealogy and History Room, and served on the board of the Lincoln County Cultural and Historical Association. In 1997 she gave the house and all its contents, along with a large archive of family letters, documents, and ephemera, to Historic New England.

Becoming a Museum, Telling the Tuckers’ Story

Becoming a Museum, Telling the Tuckers’ Story

Jane Tucker continued to live in the house until 2003 while working with Historic New England to catalogue the thousands of objects, furnishings, books, prints, costumes, and textiles contained in the house. In 2003 Historic New England opened Castle Tucker as a historic house museum.

Castle Tucker and the Tucker family collection in the Library and Archives constitute one of Historic New England’s largest single family collections. The story of the Tuckers is one of successes, trials, tribulations, and perseverance. In this house, visitors learn how one unique family survived the economic roller coaster of life on the Maine coast during the nineteenth and twentieth centuries. They see how family pride and love endured despite emotional turmoil, physical separations, and fortunes earned and lost.

Since 2007 Historic New England has employed year-round staff at Castle Tucker to maximize the opportunities offered by this home and the Tuckers’ story. We welcome an increasing number of visitors each year and look forward to finding new ways to serve our communities and members at Castle Tucker.

Hidden Outlet

Hidden Outlet First continuous contact with Europeans in Maine came in the mid-17th century with French explorers, trappers and traders interested in commerce with the Wabanaki rather than colonization. Merchant ships soon followed carrying Catholic missionaries as well as traders. English colonists began to arrive in increasing numbers in the later 17th and 18th centuries with expectations of sovereignty over all, whatever means necessary.

First continuous contact with Europeans in Maine came in the mid-17th century with French explorers, trappers and traders interested in commerce with the Wabanaki rather than colonization. Merchant ships soon followed carrying Catholic missionaries as well as traders. English colonists began to arrive in increasing numbers in the later 17th and 18th centuries with expectations of sovereignty over all, whatever means necessary. The Lees and Elm Lawn

The Lees and Elm Lawn The house had several tenants, not all of whom have been identified. Architectural changes and repairs made to the house during this period were not documented. In the 1840s and 1850s Wiscasset enjoyed another brief period of prosperity as the cotton trade invigorated shipping once again. In 1845 Franklin Clark, an ambitious local politician and successful lumber merchant, purchased the house and began what appeared to be significant renovations and changes. These probably included moving two of the house’s chimneys to the end of each semi-circular bay, replacing central windows that had previously lit those rooms. However, Clark did not have the money to pay for these changes or any other of his failed investments. He was apprehended by the local sheriff at the train station trying to leave town, fleeing his creditors.

The house had several tenants, not all of whom have been identified. Architectural changes and repairs made to the house during this period were not documented. In the 1840s and 1850s Wiscasset enjoyed another brief period of prosperity as the cotton trade invigorated shipping once again. In 1845 Franklin Clark, an ambitious local politician and successful lumber merchant, purchased the house and began what appeared to be significant renovations and changes. These probably included moving two of the house’s chimneys to the end of each semi-circular bay, replacing central windows that had previously lit those rooms. However, Clark did not have the money to pay for these changes or any other of his failed investments. He was apprehended by the local sheriff at the train station trying to leave town, fleeing his creditors.

Preservation and Presentation

Preservation and Presentation