Gropius used traditional New England building materials and architectural elements in intriguing ways, like the vertical clapboard walls of the front hall which are not only functional but beautiful. Gropius used their vertical orientation to create the illusion of height as well as a practical surface for hanging an ever-changing collection of artwork; wood is an easy surface to nail, patch, and paint. The entrance is an example of how Gropius interpreted a center entrance Colonial with a Bauhaus twist. This portico is on a diagonal that leads the visitor to the front door according to the natural approach. A glass block wall protects from wind and rain, yet allows light to permeate the entry passage as well as the interior hall. Mrs. Gropius noted that repairs were “kept to a minimum because the house was remarkably well built.” After weathering criticism and bewilderment about the house’s unusual design and materials from fellows in the local lumber yard, builder Casper Jenney of Concord was vindicated in the eyes of his colleagues after the house survived the devastating hurricane of 1938 with minimal damage.

Many of the fixtures in Gropius House were sourced from non-traditional commercial catalogues. For example, the hall sconces were ordered from hotel catalogues. On each side of the bathroom mirrors, half-chrome light bulbs redirect light to the sides and reflect light back to the mirrors. This creates flattering light, while simultaneously eliminating the need for any additional lighting shade or cover. The towel rack was installed on the hot water radiator to warm the towels, which in 1938 was an idea ahead of its time. Gropius House has four bathrooms, two on the first floor and two on the second floor; they are all plumbed on one main stack for efficiency and economy. All four bathrooms were located in the less prominent northwest corner of the house, where solar gain and views were not important.

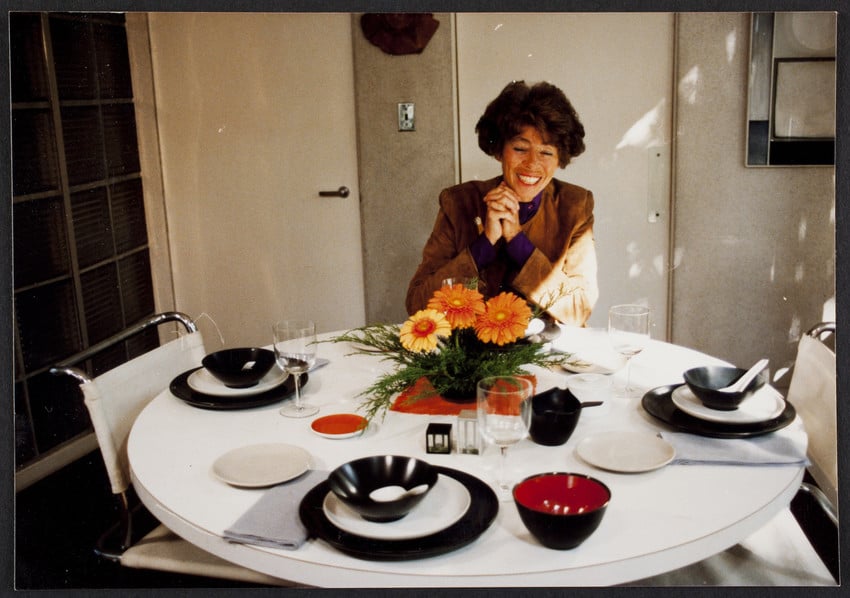

Above the Marcel Breuer-designed white Formica dining room table is a ceiling light fixture that was a type used by museums to highlight a piece of artwork. It has a particular adjustable aperture so that it illuminates only to the perimeter of the table. This dramatic lighting effect was used by the Gropiuses as part of their entertaining repertoire of sparkling dishes, floral arrangements, cast shadows, and flattering light.

Gropius experimented with non-traditional materials such as the California acoustic plaster found throughout the living and dining room walls and ceilings as well as elsewhere in the house. A very porous substance that unfortunately has “greyed” over time from its original white color, it was applied with a spray gun over the lath. Its sound-absorbing characteristics still function effectively.

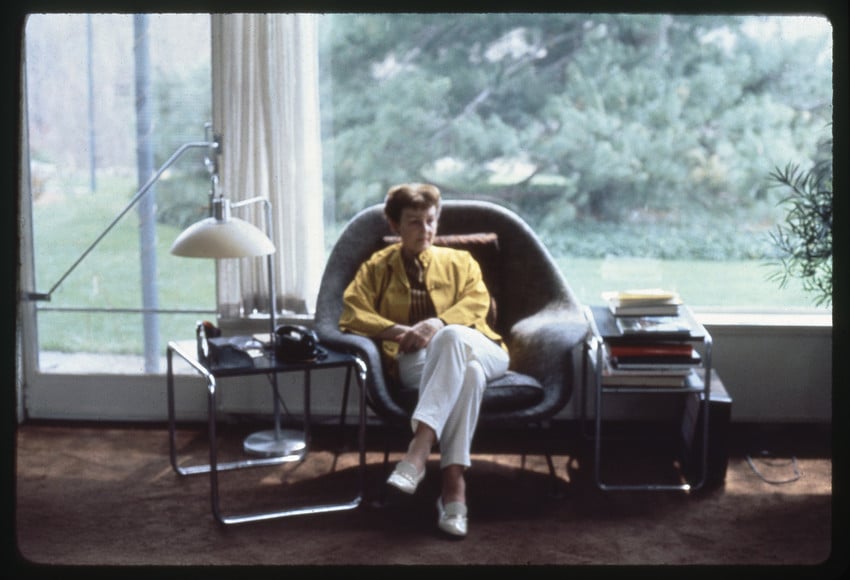

Almost all of the furniture in the house was handmade in the Bauhaus workshops in Dessau before the family left Germany. There are a few notable exceptions, including the Saarinen womb chair and the Sori Yanagi butterfly footstools in the living room. Ise purchased the two-seat TECTA sofa in the living room in 1975 from Germany.

Guests to the Gropiuses’ home and dinner table included their Bauhaus friends and fellow émigrés as well as other notables of the twentieth century. Alexander Calder, Joan Miro, Igor Stravinsky, Henry Moore, Demetri Hadzi, and Frank Lloyd Wright are a few names in the Gropius guestbook.

In several ways, Gropius incorporated the philosophy of living in harmony with nature. The large plate glass windows have a dual purpose: they visually bring the outdoors in, but also permit passive solar gain. Another strategy he used was to allow the flat roof rainwater and snow melt to drain through a center pipe to a dry well. Over time, Mrs. Gropius designed her gardens to become low-water, low-maintenance, and incorporated indigenous plants. They did not have air conditioning, but used passive ventilation.

Walter Gropius believed that the relationship of a house to its landscape was of paramount importance, and he designed the grounds of the home as carefully as the structure itself. In 1938 the Gropiuses enjoyed sweeping views because the house stood alone on top of the hill unobstructed by trees and woods. The grassy plinth on which the house sits is defined by stone walls. This “civilized area” around the house included a lawn extending roughly twenty feet around the house and a perennial garden that continued the thrust of the south-facing screen porch. Beyond the well-tended ring, the apple orchard and meadow were left to grow naturally. For new trees, the Gropiuses selected Scotch pine, white pine, elm, oak, and American beech.

Wooden trellises reaching from the east and west sides of the house and covered with roses and vines offered privacy and protection from the road. Vines such as bittersweet, Concord grape, and trumpet vine were planted to link the house to the landscape. The Gropiuses’ goal was to create a New England landscape, complete with mature trees, rambling stone walls, and rescued boulders as focal points.

The Japanese-inspired garden in the back of the house was installed by Mrs. Gropius in 1957 after a trip to Asia. It was her intention to create a low-horizon profile in the garden with azaleas, cotoneasters, candytuft, and junipers, and to use a red maple as the focal point under the arch.

Walter and Ise Gropius considered the screened porch to be among the best practical New England responses to the environment. However, they noted, porches usually darkened interior living spaces and were often placed at the front or side of a house. In past decades a porch overlooking the road would be quite pleasant, with neighbors and infrequent slow-moving vehicles passing by. However, modern living dictated that a porch should not force the occupants of the house to endure the noise of the street. Gropius adapted the basic idea, placing the porch perpendicular to the house to capture every available breeze, provide total privacy from the road, and darken only a service room. The screened porch room permitted outdoor living year round. Mr. Gropius played ping pong there in the winter months, as the south and west-facing sun would warm it in winter, and the breezes would cool it in summer.

On the advice of Mrs. Storrow, the garage was placed at the foot of the driveway to the left of the entrance. This was a distance from the house, but convenient for minimizing snow shoveling in winter. It also provided an unobstructed view of the main structure. After Mrs. Storrow’s death in 1945, the Gropiuses bought the house from her son, and added one and a half acres to the original four acres.

Prior to early European settlement in the seventeenth century, this land was home to the Nipmuc people who are descendants of the indigenous Algonquian people. They call the Concord area (which includes modern day Lincoln) by the name Musketaquid [Muss-ka-ta-quid] or Marsh Grass River.

Prior to early European settlement in the seventeenth century, this land was home to the Nipmuc people who are descendants of the indigenous Algonquian people. They call the Concord area (which includes modern day Lincoln) by the name Musketaquid [Muss-ka-ta-quid] or Marsh Grass River. Originally part of Concord, Lincoln was settled by Europeans in 1654. The town of Lincoln was formed a century later when inhabitants of the southeast section of Concord petitioned for a separate town so that they could have a more convenient place of public worship located in their own town center.

Originally part of Concord, Lincoln was settled by Europeans in 1654. The town of Lincoln was formed a century later when inhabitants of the southeast section of Concord petitioned for a separate town so that they could have a more convenient place of public worship located in their own town center. In the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, Lincoln was primarily agrarian with other local enterprises. Roads and the new railroad made an impact on the local economy, facilitating more movement of goods and people. The Lincoln station train stop was established before 1850. Lincoln was previously home to a second railroad station, the Baker Bridge station, which was the site of a deadly 1905 train wreck. The railroad brought wealthy Bostonians who built their country estates in Lincoln.

In the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, Lincoln was primarily agrarian with other local enterprises. Roads and the new railroad made an impact on the local economy, facilitating more movement of goods and people. The Lincoln station train stop was established before 1850. Lincoln was previously home to a second railroad station, the Baker Bridge station, which was the site of a deadly 1905 train wreck. The railroad brought wealthy Bostonians who built their country estates in Lincoln. Alexander Henry Higginson was the son of Boston Symphony Orchestra founder Henry Higginson, who bought Alexander land in Lincoln to fulfill his interest in fox hunting and steeplechase. The younger Higginson built an imposing Tudor-style estate on Baker Farm Road in 1906. Today the Higginson Estate houses the Thoreau Society.

Alexander Henry Higginson was the son of Boston Symphony Orchestra founder Henry Higginson, who bought Alexander land in Lincoln to fulfill his interest in fox hunting and steeplechase. The younger Higginson built an imposing Tudor-style estate on Baker Farm Road in 1906. Today the Higginson Estate houses the Thoreau Society. A Family Home in Lincoln

A Family Home in Lincoln Gropius’s Intent

Gropius’s Intent Becoming a Museum

Becoming a Museum