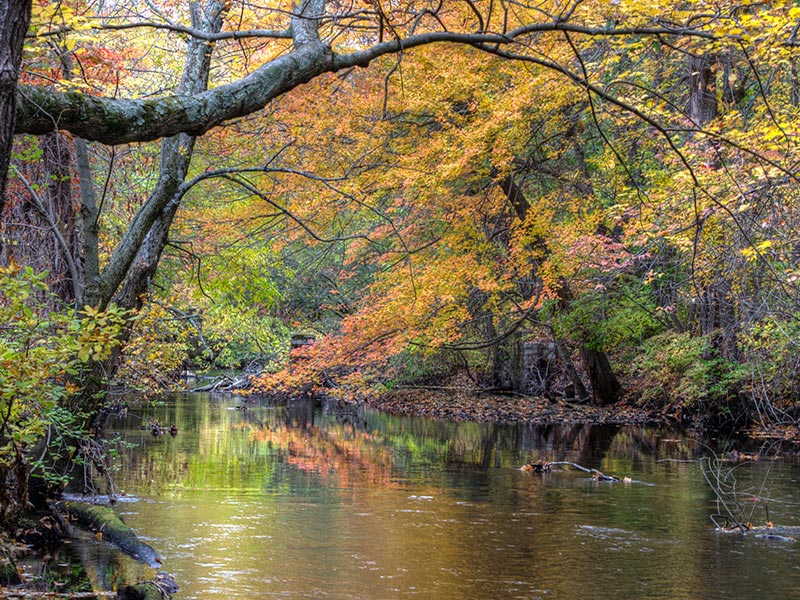

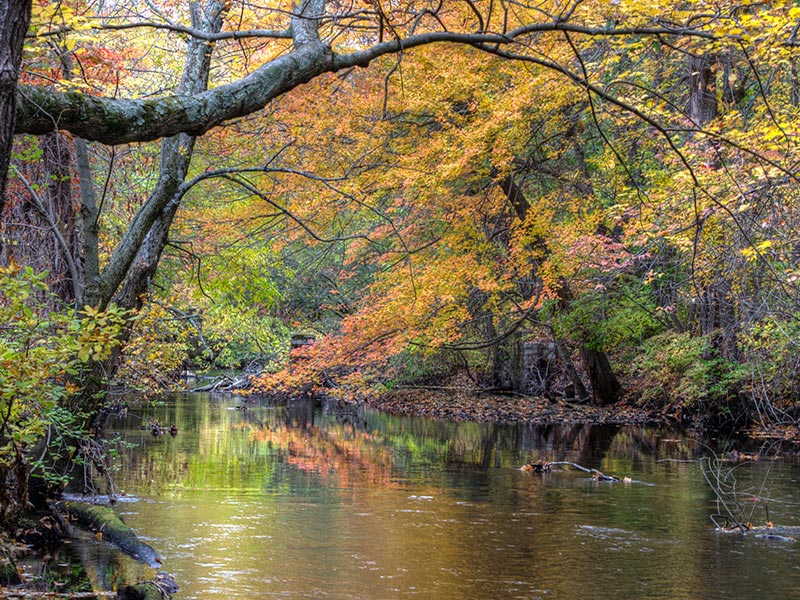

A Brook that Leads to the Woonasquatucket

A Brook that Leads to the Woonasquatucket

Indigenous Peoples have lived on what is now called the State of Rhode Island for thousands of years and they are still here. Particularly along the waterways, First Peoples including the Narragansett and Nipmuck tribes, occupied the area known today as Johnston. Thomas Clemence, a friend of Roger Williams, officially bought the property where Clemence-Irons House is now located, then part of Providence, on January 9, 1651, from an indigenous person named Wissowyamake, but according to the tax lists, Thomas Clemence was already living on the property by 1650.

Archeology shows significant evidence of Indigenous People living and hunting on the small fraction that remains of the original property. This activity is universally believed to be due to the brook on site that leads directly to the ancient and important Woonasquatucket River.

Clemence Family

Clemence Family

This eight-acre parcel of meadow lying along the Woonasquatucket River, originally part of Providence, was increased during the 1670s and 1680s. Through additional purchases and land grants from the initial land divisions of the town of Providence, Thomas accumulated at least one hundred and ten acres. Thomas Clemence became an influential member of the community soon after his arrival from England in 1636 and was one of the original purchasers of the town of Providence. He was chosen to represent Providence at the Court of Commissioners in 1663, and a Court of Deputies in 1665 and 1671. In 1667 he was chosen as town treasurer. He was one of twenty-seven men who stayed when residents of Providence were moved to Newport during King Philip’s War in 1675 and 1676. He also had a house that was destroyed during this conflict. Although it is popular lore that the existing chimney belonged to that house and a new house was built to incorporate it, it is likely that the house that burned was located in what is now downtown Providence. Thomas accumulated acreage and improved it so it could be farmed, as did the next two generations of Clemence yeomen. Thomas and his wife Elizabeth had four children.

In 1681 Thomas Clemence left this property to his son Richard, for whom what is now known as Clemence-Irons House was built in 1691. It is difficult to know for sure the original plan of the house, but the most popular theory, and the basis of the later restoration, was that it was built as a story-and-a-half structure with a rear lean-to, a large stone-end chimney, topped with a steep gable roof. Four small rooms (great room, kitchen, principal chamber, and smaller chamber) were located on the first floor, with a cellar below and a garret chamber above. As is typical of the Rhode Island stone-ender, the chimney occupies most of the west side of the structure. In this country, stone-enders are unique to Rhode Island. It is a building form that can be traced back to Wales, Sussex, and western counties of England, where building in stone was the tradition. It is thought that the early colonists of the area built their houses in styles they knew. Clemence-Irons House seems to be an adaptation of a modest English Tudor cottage, right down to the stonework of the Elizabethan-style chimney.

When Richard Clemence died in 1723, he in turn granted the property, which now encompassed 300 acres, to his son Thomas. At the time, the property included the homestead of meadows and tenements located along the banks of the Woonasquotucket River. This was the first time a building was mentioned on the property.

Angell Family

Angell Family

Thomas Clemence sold the property to John Angell in 1740. The size of the farm had increased to 300 acres with housing, fences, a corn crib, a bar, a shop, and improvements. Upon the death of John Angell, the farm was passed to his son James. By the time the property was sold after James’s death the size of the farm had increased to over 370 acres. This appears to be the most land that ever existed within the Clemence-Irons homestead. The property stayed in the Angell family for three generations.

It is quite apparent that the first two generations of Angells did not live on the property. They both lived on their homestead in the center of Providence. Even though records could not be found, it is very probable that they leased it out to be farmed. The third generation of Angells did live here for a short while and it is clear that John Angell did work the land himself.

As textile mills flourished and expanded, the size of many farms decreased as the valuable property along the river was leased or sold for industrial purposes. The first record of any agreement concerning industry and the Clemence-Irons property was in 1807 when William and Abigail Angell Goddard signed an agreement with the Lyman Manufacturing Company giving the company limited rights to the use of the water and land along the river’s edge and their property. This arrangement seems to have been renewed annually and continued on after the Goddards sold the land to Stephen Sweet in 1826.

Johnston, RI

Sweet-Irons Family

In 1826 Stephen Sweet bought the property, which now consisted of 300 acres. He immediately sold most of the parcel to George Waterman, a cotton manufacturer, leaving approximately 100 acres for his own use. Sweet farmed the property until his death in 1855, when the farm was partitioned among his heirs. His daughter Sarah Manton, wife of Amasa Irons, became owner of the homestead, barns, and other buildings, and about fifteen acres of land extending easterly to the Woonasquatucket river. By the middle of the nineteenth century, the Clemence-Irons property was surrounded by industry and its by-products: to the east was the Lyman Factory Pond and the dam, to the south was the Killingly Road, to the west was the Widow Sweet’s Factory, and to the north was George Waterman’s factory.

Miss Ellen E. Irons (1862-1937)

Ellen Irons, known in her youth as Nellie, was born in 1862, during the Civil War, and died in 1938, before the country had fully recovered from the Great Depression; the latter partially factored into the dire financial situation that she found herself in at the end of her life. She was the last owner/occupant of Clemence-Irons House. Irons was a respected schoolteacher, piano instructor, leader in her local church and the temperance movement, landlord, and a single woman who reared an unrelated child from infancy until age seven.

Ellen attended the Providence Normal School, which was a leader in training future educators; however, she attended sporadically and did not graduate. That apparently was not a setback; during her twenties and thirties she worked as a schoolteacher. However in 1897, discussions began to take hold regarding the need for increased teacher certification requirements. Irons’s career was at risk, but the grateful parents of her former students came to her defense. On October 15, 1897, this notice appeared in the Olneyville Times: “Miss Ellen Irons, a former teacher in the Sisson St. School, Providence, received a testimonial as to the satisfactory qualities of her work signed by sixty-five of the parents from that school.” Unfortunately, in 1898 Rhode Island legislators passed a law requiring stricter guidelines for teacher certification. Irons was last employed as a teacher during the 1897–1898 school year. She was in her mid-thirties and single, her parents had died, and henceforth she supported herself by continuing to take in boarders, as her family had done for years. Also, she sold parcels of the small acreage that she had inherited.

Tenants/Boarders at Clemence-Irons House

State and federal census records show that the Irons house on George Waterman Road was almost always filled with people, including family members, a few occupants listed as servants, and often many boarders. For example, Rhode Island’s 1875 state census lists twelve-year-old Ellen along with five family members; a twenty-five-year-old boarder named Frank Holland, who was a listed as a white farmer originally from Illinois; a boarder named Alexander Hammond, also twenty-five, who was a Black farmer originally from Westerly, Rhode Island; and fifty-eight-year-old Ruth Williams, a white servant who had come from England.

The 1910 federal census shows Irons hosting two widowed boarders, one in her seventies and the other in her eighties. The 1920 federal census lists an Italian immigrant family of eight boarding in the rear of the house with Irons, who then was fifty-eight years old. At this time, Italian immigrants Ralph and Annett Raffatory (incorrectly transcribed; further research points to the last name of the family as D’orio or Diorio) had six children; the eldest was sixteen years old and the youngest was eighteen months.

Perhaps the most interesting account of Irons’s boarders appears in the 1900 federal census. In this record, thirty-seven year old Ellen is listed living with eight-month-old Wilhelmina Peppers, who is described as white and a “boarder.” Research shows that Wilhelmina’s parents, George Warren Peppers and Lillie May Tittle, were married in Providence three months before Wilhelmina’s birth. In the same census, Mr. and Mrs. Peppers are living on the North Shore of Massachusetts and recorded as ages sixty-eight and thirty-five respectively. The arrangement raises questions, though whatever the answers, Irons raised Wilhelmina on her own until the girl was seven. This was two years after the child’s father, whose occupation was listed as “capitalist,” had died. The August 16, 1907, edition of the Olneyville Times of Providence reported that “Miss Wilhelmina Peppers who has lived some time with Miss Ellen Irons is about to go to Boston to reside.” Also, Ellen apparently maintained a relationship with Wilhelmina. The November 20, 1908, edition of the same newspaper states, “Miss Ellen Irons visited Miss Lillie Pepper at her home in Beverly Mass this week.”

The impact of the Great Depression coupled with Irons’s lack of any substantial income for many years led her to take out a mortgage on her house. She did receive some assistance from the Rhode Island Department of Public Welfare, Division of Old Age Security during the last years of her life. After Ellen Irons died, her house was ordered to be sold for no less than $2,200, the sum of her debts, which included a heating bill, funeral expenses, and the mortgage. By this time the land had gone through two subdivisions and amounted to less than an acre. Siblings Ellen Sharpe, Henry Sharpe, and Louisa Sharpe Metcalf, scions of a wealthy, philanthropic Rhode Island industrialist family, purchased the property.

Restoration by Norman Isham

Restoration by Norman Isham

The house was purchased by Henry D. Sharpe and his sisters Ellen and Louisa with the intent of restoring it to a seventeenth-century structure. By this time the house had grown to thirteen rooms, including a one-story room at the east end with a corner fireplace, used as a parlor; a story-and-a-half rear lean-to, containing a kitchen, bathroom, and a stair hall in the first story, and two bedrooms in the above story; a one-story ell at the northwest corner; and a front hall and porch at the southwest corner. Early photographs document the existence of several outbuildings on the property. Also removed prior to or during the restoration were at least two one-and-a-half-story gable roofed barns close to the southwest corner of the house, and a small shed that stood just north of the barn. The Sharpes hired Norman Isham, a leading scholar of colonial architecture and co-author of Early Rhode Island Houses (1895), to restore the house.

During the restoration, which began in 1938, everything that was not original to the house was removed, namely the roof, dormers, doors and windows, dormer, plaster, lathe, and layers of wallpaper. Some of the early interior alterations that were removed from the house included the brick oven adjoining the kitchen fireplace, a paneled fireplace, a vaulted plaster ceiling from the northwest ell, and all interior room partitions. Uncovered during the removal phase was the original paneling on the walls, found under the many layers of lath, plaster, and wallpaper. What was left was the bare framing of the house, comprising massive oak timbers with decorative chamfering, mortised and tenoned together, and the massive stone chimney.

The house was recreated with a four-room, one-and-a-half-story plan. The entrance leads directly into the hall, a fifteen-foot square room with a huge fireplace across its west end, with a small staircase beside it leading to the garret. A fifteen- by seven-foot bedroom chamber adjoins the great room in the front of the house. The rear lean-to consists of two rooms: the kitchen and a small bedroom chamber. The stone fireplace built into the west wall of the kitchen was constructed as part of the restoration.

On the exterior, sash windows were replaced with smaller casements with leaded glass panes. The replacement doors were made from a triple thickness of planks nailed together by knob-headed nails, hand-hewn clapboards were made for the exterior walls, and shingles split for the roof. In the interior are only the massive timbers used in construction and the two large fireplaces. The walls are adorned only by beaded wall sheathing and the chamfers of the timbers themselves. After the restoration was completed, more than half of the materials present were new. The reconstruction of much of the materials is so precise it is difficult to determine what is original and what has been replaced.

This method of restoration, though it differs from current philosophies, was thought to be one of purity and accuracy. Both Isham and Cady were active very early in the history of architectural restoration in this country and both were very highly respected. In addition to being members of the American Institute of Architects, Isham was the foremost expert of his day in colonial architecture and Cady was an accomplished Rhode Island historian. They made sure that materials used in the reconstruction were those of seventeenth-century craftsmanship and hired Joseph H. Bullock, a specialist in early building methods, to oversee the process.

The effect of the recreation was made complete with period reproduction furnishings. These include a long trestle table, a set of turned ladder back chairs and a settle for the hall, a hutch for the kitchen, and a chest and beds for the two downstairs chambers. These furnishings are not characteristic of what would be found in a home of such an early date and are part of the romantic recreation of Sharpe and Isham. Through the funding of Henry Sharpe, Isham had the opportunity to recreate a small piece of seventeenth-century Rhode Island.

Front levation, general conditions, Clemence-Irons House, Johnston, RI, March 13, 2006.

Becoming a Museum

After the restoration was complete, the Sharpes opened the house to the public, and in 1947 gave it to Historic New England, then the Society for the Preservation of New England Antiquities. Historic New England maintains the property as a museum, open to the public periodically throughout the year.

A Brook that Leads to the Woonasquatucket

A Brook that Leads to the Woonasquatucket Clemence Family

Clemence Family Angell Family

Angell Family

Restoration by Norman Isham

Restoration by Norman Isham