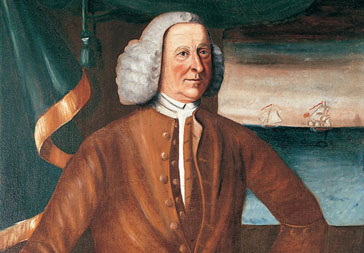

Jonathan Sayward referred to himself in deeds and other documents as a trader, a coaster, and a mariner. In 1744 Governor William Shirley of Massachusetts commissioned him to command the sloop Sea Flower in the expedition against Cape Breton Island, Nova Scotia, which resulted in the capture of the French fortress of Louisburg in 1745. By about 1760 Sayward had built up a substantial shipping business, and in succeeding years he was involved in the lumber trade with the West Indies and the fur trade with Canada. He sponsored ships voyages to the West Indies trading in enslaved people.

His business contacts were strengthened by the marriage of his only child, Sarah, to the aspiring merchant Nathaniel Barrell – a brother of the better-known Boston merchant Joseph Barrell. In 1763 Nathaniel and Sarah Barrell (or Sally, as she was called) moved a few miles up the York River from Sayward-Wheeler House to a farm Sayward owned on Beech Ridge.

As Sayward’s wealth grew, so did his civic involvement. In 1761 he was appointed Justice of the Peace, in 1768 Justice of the Quorum, and from 1766 to 1768 he was given the great honor of representing York in the General Court in Boston.

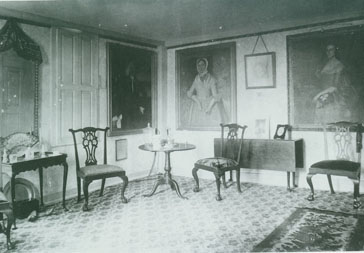

Sayward made improvements to the residence. According to the diary he began in 1760 and kept almost until his death, in November 1761 he paid £45 to Samuel Sewell, a local joiner, for work on the house. This work probably included installing the paneling, which survives in the parlor and the chamber above it. He added a first-floor bedroom and a new kitchen, converting the old kitchen into a sitting room.

A turning point for Sayward and the American Colonies came in June 1768, when the General Court took a vote on whether or not to rescind a letter it had issued the winter before inviting the other colonial governments to join Massachusetts in forming a common body to oppose certain British duties and taxes. The letter was a clear sign of growing colonial resistance to British rule and the royal government ordered it be rescinded. Sayward was pessimistic about the ability of the colonies to unite and he feared they would pay dearly at the hands of the mother country should they try. He had opposed the letter and was among only seventeen of the 107 members of the General Court who voted to rescind, as the royal governor ordered. The seventeen “Rescinders,” as they were called, came under bitter attack in newspapers, broadsides, and caricatures. Sayward wrote in his diary, “we are treated with all contempt.” In a drawing by Paul Revere, the “Rescinders,” including Sayward, were caricatured being driven into hell by the devil.

Not surprisingly, Sayward was not re-elected to the General Court after this incident, but he continued his civic involvement, serving as both Special Justice of the Court of Common Pleas and Judge Probate of York County in the 1770s. During these years, Sayward’s diary entries reflect his continued dismay at the disrespect shown the royal government in Massachusetts and his growing worries about the future of the colonies. Sayward was particularly upset by the Boston Tea Party of December 1773 and argued vehemently against York’s approval of the “actions in Boston” in a two-day town meeting. He even sparred good-naturedly with the visiting John Adams during a dinner party in York later that year, urging Adams to be cautious in his “expedition to Congress.”

During this time, at least one enslaved man, Cato, was living and working at the household. In 1769, Cato attempted to escape but was recaptured.

By 1773, a second enslaved man, Prince, was living and working at the household. A young, enslaved woman, Dinah, was living and working at the Robert Rose Tavern, a little over one mile from the house.

In the 1770s, Prince, Cato, and Dinah would have been exposed to heated discussion and rising excitement about liberty and independence from England, and to actual conflicts between American colonists and British military in Portsmouth.

In essence a Loyalist, Sayward’s personal safety was in danger as revolutionary fervor grew. He narrowly eluded harm on a number of occasions. In October 1774, for example, Sayward heard a rumor that he was to be “mobbed.”

Sayward described 1775 as a “year of many trials.” It was a year in which his wife of thirty-nine years, Sarah Mitchell Sayward died, he was stripped of his civic positions, and he was sequestered in York. His confinement restricted his ability to conduct business and his finances suffered. He wrote in his diary on May 12, 1777, “I heard the Clock every Hour last night. Little or no Sleep.”

In 1780, Prince and Dinah were married. In 1781, Prince achieved manumission by enlisting with the Continental Army—without Sayward’s consent.

In 1779 Sayward married his second wife, Elizabeth Plummer of Gloucester, Massachusetts. In the 1780s and 1790s he often visited friends in Boston and entertained others at his house in York. He noted in his diary in 1788 that his estate was diminishing, but he continued to take on apprentices to work in his warehouses. One of these was his eldest grandson and namesake, Jonathan Sayward Barrell, who attended Dummer Academy in Newbury, Massachusetts, and then returned to York in 1786 to work for his grandfather. In 1795 Sayward Barrell, as he was called, married Elizabeth Sayward’s niece Mary Plummer, and set out to establish himself as a prosperous merchant.

In 1783, Prince returned from the war a free man and found employment. Prince and Dinah lived in a dwelling near the Sayward household. According to his diary, Sayward had the house constructed for them.

In the same year, Cato purchased his freedom from Sayward for $275.

Prince died of tuberculosis in 1789. Dinah never remarried. She applied for and received a widow’s pension 49 years later, in 1838. She died in an alms house in York at the age of 101, in 1845.

There is as yet no information about Cato’s life after achieving manumission. Because the name Cato was a common among enslaved males of the era, and because Cato was deprived of a surname, research is difficult.

Having married his second wife, Elizabeth Plummer in 1779, Sayward died in 1797. He left the house and its contents to his grandson and namesake, Jonathan Sayward Barrell who, married Elizabeth Plummer Sayward’s niece Mary Plummer, set out to establish himself as a prosperous merchant.

Agamenticus

Agamenticus Prosperity and Politics

Prosperity and Politics Poverty, Veneration, and Preservation

Poverty, Veneration, and Preservation