Naumkeag

Prior to the seventeenth-century English colonization, the land now called Salem was and is the ancestral home to the Naumkeag band of the Massachusett tribe. Naumkeag, both the traditional name of the land and the people who lived there, was seasonally rich in resources. By living with the land in this way, the Naumkeag were semi-nomadic and traveled to nearby hunting and fishing grounds with environmental changes.

By the early 1600s, the thriving community dealt with war and disease that severely diminished the Naumkeag population. Continual clashes with the Micmac to the north resulted in many casualties, including that of Nanapeshamet, the Naumkeag sagamore or chief. Simultaneously, the Naumkeag’s numbers were further reduced by an epidemic that spread through coastal New England from 1616 to 1619 due to the introduction of European diseases. Because the indigenous people had no prior exposure, they had no resistance to fight the contagion, which spread rapidly throughout the community. Historian Emerson Baker concludes that by 1631, there were roughly only three hundred indigenous people between the Mystic River and Naumkeag, whereas before 1616, the population was in the 20,000s. Continued interaction with Europeans led to a smallpox epidemic in 1633, which further decreased the Naumkeag population.

The first European to settle in Naumkeag was Roger Conant, who led a group of men from a failed colony in Cape Ann in 1626. Two years later, John Endicott arrived with a charter from the New England Company (which would become the Massachusetts Bay Company). Conant and Endicott’s groups combined and by 1629, the English called the land “Salem,” an anglicized spelling of shalom, the Hebrew word for peace.

While the English and Naumkeag lived relatively harmoniously, however, the English saw the land as empty and available for the taking. The cleared expanses and lack of permanent structures belied the many years of land use by the Naumkeag. The English imposed their farming practices, replacing the traditional crops, and permanent dwellings were built.

In the second half of the 1600s, the English exerted more control over the land. In 1644, the sachems signed over their lands and people to the governance of the Massachusetts Bay Colony and after that time indigenous people had to appeal to the English court system to retain ownership of their land. Tensions continued to mount by the 1670s, and during King Philip’s War, the English fortified their settlement and in 1679 the town ordered that no indigenous person could spend the night in Salem.

In 1686, Bartholomew Gedney, brother to Eleazer Gedney who built Gedney House, took testimony from James Rumney Marsh, a nephew of Sagamore George, the sachem of the Massachusett, about Salem’s geographic boundaries. Gedney and his fellow Salem selectmen purchased the land that is now Salem, Danvers, and Peabody from Sagamore George’s family on October 11, 1686 for £20. The deed noted that “said land is part of what belonged to the Ancestors of the Grantors and is their proper inheritance.” This deed included the land that Gedney House now sits upon.

Building Gedney House

On April 20, 1664, Eleazer Gedney, a wealthy shipwright, purchased a half-mile tract of land in Salem on the highway from Marblehead, know today as High Street. In anticipation to his marriage to Elizabeth Turner, the sister of the John Turner who would build the House of the Seven Gables in 1668, he began construction on the earliest portion of his home. The house was a typical seventeenth-century timber-frame structure with two main rooms on either side of a central chimney. Atypical features included an attic with a large facade gable and a parlor with a lean-to roof. Other features, mentioned in Gedney’s probate inventory from June 25, 1683, included a hall chamber, garret, kitchen loft, and “seller.” After Gedney’s death, his second wife, Mary Patteshall, resided in the house with the couple’s children. The probate records indicate financial hardship to the family and therefore it is likely that there were no major architectural changes made while Mary Gedney owned the property.

Gedney House and the Salem Witch Trials

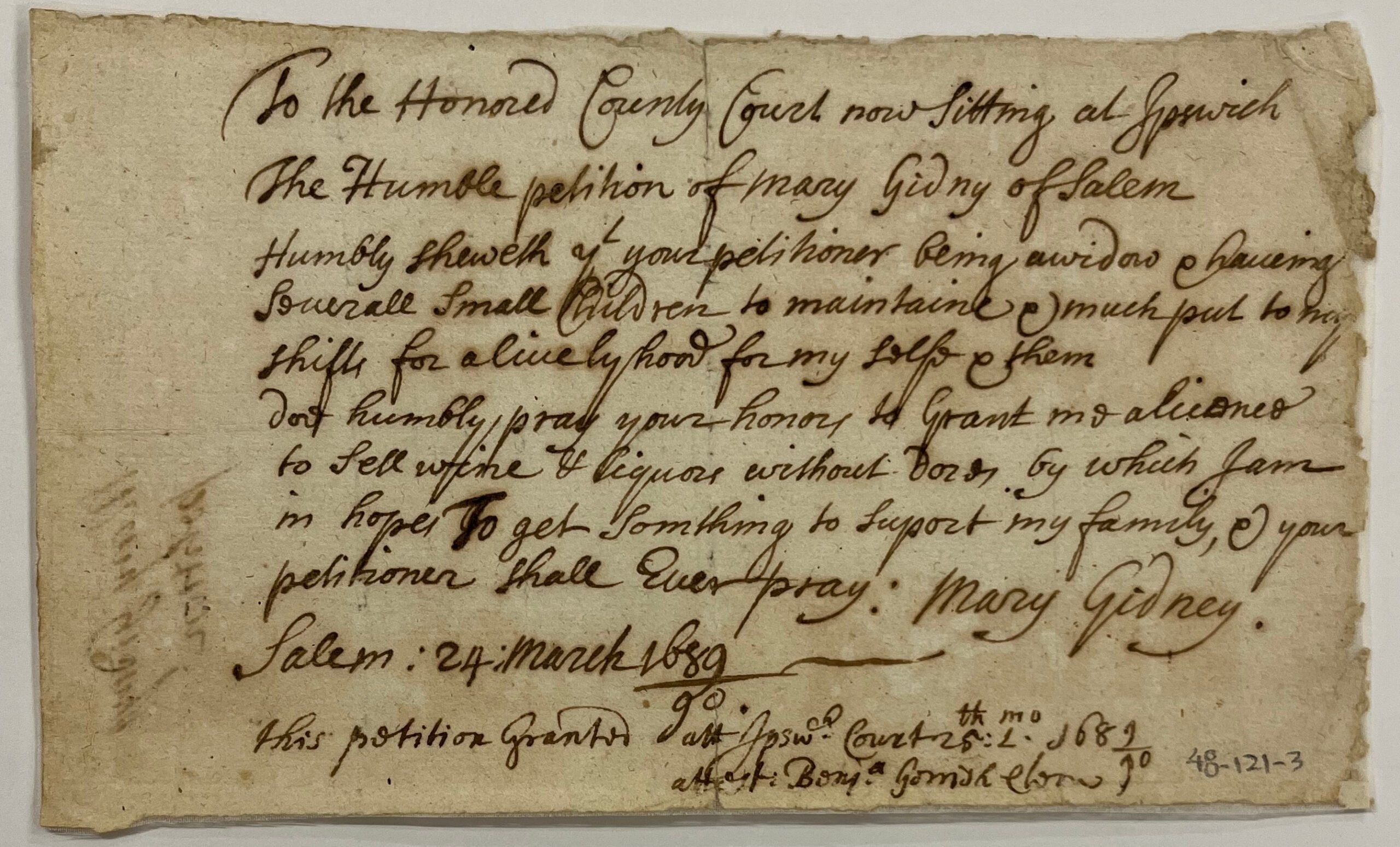

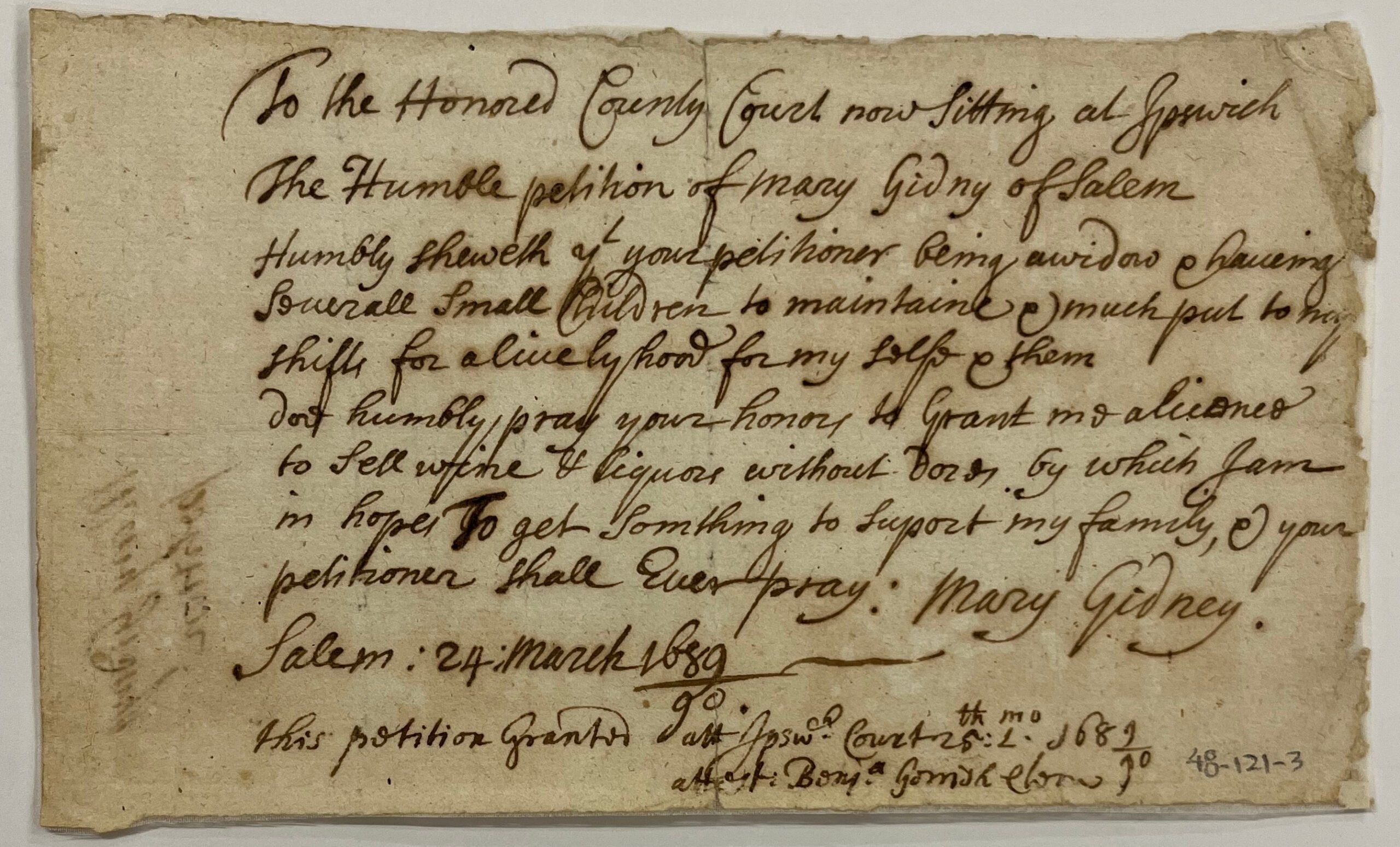

Mary Gedney did not remarry following Eleazer’s death, but instead requested a license from the county court to sell wine and liquor out of doors in the hopes of independently supporting her family. Her home was in a prime location, by the waterfront and on the highway to Marblehead. The request was granted in 1690.

Mary expanded her business by July of 1692, and received approval from Salem selectmen to be an innholder, allowing her to rent out rooms as well as sell meals and drinks inside her home. This allowance was granted during a crucial time in Salem’s history. Between February 1692 and April 1693, private homes and taverns were being used to conduct official proceedings for the infamous Salem Witch Trials. By the time Mary received her innholder license, six people had already been executed for witchcraft, with many of the proceedings being presided on by her brother-in-law, Witch Trial judge, Bartholomew Gedney. While it is not known how large a role Mary Gedney’s tavern played during the Witch Trials, court documents reveal that the tavern was used “for entertainment of jurors and witnesses.”

Owning and operating a tavern was a way for Mary to keep her societal value and independence as a widow during the seventeenth century. By remaining unmarried, Mary was able to retain Gedney House in her name and was able to support herself and young family. When Mary Gedney died in September 1716, her estate was administered by her daughter, Martha, and son-in-law, James Ruck, who inherited the house.

Mary Gedney’s petition, 1690. Massachusetts Supreme Judicial Court Archives, Massachusetts Archives. Boston, MA.

Changes on High Street

The Gedney’s youngest daughter Martha, born in 1682, married James Ruck in 1712. Ruck, also a well-to-do shipwright, moved to Gedney House at this time. Because of the improved financial status and stability that the marriage brought to the family, it is likely that the first major renovations occurred around this time. The lean-to was raised, a second story, and overhang were added to the north elevation of the property, and the façade gable was removed. The house was left to their only child, Mary, in 1739. Her child, Gedney King, sold the property to Benjamin Cox, a fisherman, in 1773, ending the Gedneys’ ownership of the property.

Benjamin Cox likely built the small cottage behind Gedney House c. 1775. From 1773 on, the property was used as an investment property for a chain of absentee owners. Around this time, the central chimney was decreased in size and an addition was added to the west elevation of the house, likely to add rentable space. Throughout the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, the interior went through numerous changes. The property was used through 1962 as rental property in what would become Salem’s Italian-American immigrant neighborhood.

Center of Two Communities

Center of Two Communities

After 1773, the house was owned by a string of absentee landlords, with an increasing number of families occupying the building. The back portion of Gedney House was built in approximately 1800 as rental space. There were at least two extra living spaces in this back part of the house where you can see an entry door, extra staircases, areas for a stove pipe, and openings for plumbing.

In the 19th century, the area surrounding Gedney House was known as “Roast Meat Hill,” one of Salem’s African American communities. A successful and active Black community grew here in the 19th century, with some people owing businesses, working as laborers and seafarers, and serving as active members in the abolitionist movement.

In June of 1914, a fire swept through Salem, destroying much of the area around Gedney House. The neighborhood rebuilt on and around High Street was home to Italian immigrants coming to Salem at the beginning of the 20th century. In the center of Salem’s “Little Italy,” Gedney House was divided to accommodate multiple families. By the second quarter of the 20th century, the house was considered a tenement, with overcrowding and poor living conditions. In 1940, there were four households living here, which equated to about 25 people.

The neighborhood provided the Italian-American community with a support network and connections to their traditions. The heart of the community was St. Mary’s Church, located on Margin Street. There were Italian bakeries and produce carts, barber shops, and local businesses run by neighbors. It was a thriving area of Salem up through the Second World War.

Becoming a Museum

Becoming a Museum

Fred Winter of Marblehead purchased the High Street properties in 1962 for conversion into apartments. Elizabeth Butler Frothingham, a student of Abbott Lowell Cummings at Boston University, is credited with the rediscovery of Gedney House in 1967. While walking home from the train station, which was located in today’s Riley Plaza at the foot High Street, she noticed piles of eighteenth-century paneling on the curb for trash pick-up. As Frothingham investigated what she believed was a poor preservation practice in an eighteenth-century property, she quickly learned that the historic fabric of a seventeenth-century house was what was actually being demolished. After the acquisition of the house from Winter by Historic New England, the house was left in the condition it was found and is considered “an unparalleled opportunity for making available to all students all the many structural secrets normally concealed in a finished house.”

Through the years, Historic New England completed dendrochronology on the house, framed drawings that detail the elaborate joinery, added lighting that highlights the early paint treatments and important architectural details, and executed supportive structural repairs. Once valued solely for its architectural significance, the house and its history is being reexamined and placed into a larger context as part of Historic New England’s Recovering New England’s Voices initiative.

Center of Two Communities

Center of Two Communities Becoming a Museum

Becoming a Museum